- Home

- Robert F. Schulkers

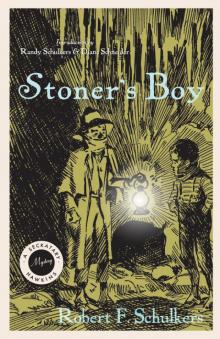

Stoner's Boy

Stoner's Boy Read online

Stoner’s Boy

Stoner’s Boy

A Seckatary Hawkins Mystery

ROBERT F. SCHULKERS

INTRODUCTION BY

RANDY SCHULKERS

AND DIANE SCHNEIDER

Illustrations by

Carll B. Williams

Copyright © 1921, 1926 by Robert F. Schulkers

Copyright © 2016 by Randy Schulkers

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-6791-6 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6793-0 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6792-3 (epub)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

To

JBD

my valentine

THE BEST BOYS’ STORIES YOU EVER READ

Contents

Introduction

Prologue

1. The Coming of the Gray Ghost

2. Stoner’s Boy Visits Pelham

3. A New Captain

4. Stoner’s Boy Hard to Catch

5. The Sheep Raider

6. Return of the Skinny Guy

7. Lost Sheep Located

8. Pursuit in the Cave

9. The Houseboat Fire

10. Stoner’s Boy Shows His Face

11. The Stolen Kite

12. Stoner’s Boy Rescues His Pal

13. The Light on the Cliff

14. Link Taken Prisoner

15. Stoner’s Cave Found

16. The Spider Web

17. The Spider Floats

18. How Briggen Was Rescued

19. Plot for Revenge Fails

20. The Twins Meet Stoner

21. Harold Bluffs Stoner

22. Stoner’s Boy Is Captured

23. The Arrow Mystery

24. Rescued by His Pals

25. Trapped in a Tree

26. What the Spy Saw

27. The Barrel Mystery Solved

28. A Job Hawkins Didn’t Like

29. Tree Mystery Revealed

30. Trapped in the Tunnel

31. Auto Thief Captured

32. Stoner’s Lair Visited

33. Stoner’s Boy Disappears

34. Robby Saves the Day

Acknowledgments

List of Contributors

Introduction

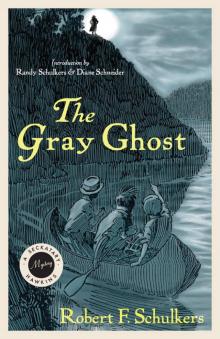

Harper Lee fell in love with the Seckatary Hawkins books as a young girl, when she used to smuggle her brother Edwin’s copies out of his room to read them secretly. The Gray Ghost and Stoner’s Boy, two books in the Seckatary Hawkins series by Robert Franc Schulkers, are frequently quoted references in her famous masterpiece, To Kill a Mockingbird. People who have read her classic are often shocked to discover that Harper Lee expressed the moral heart of all the Seckatary Hawkins books by choosing to end her unparalleled classic with a lesson from The Gray Ghost. Harper Lee remained a beloved member of the Seckatary Hawkins Club her whole life.

Schulkers, the author of forty-one Seckatary Hawkins stories, was born at home in 1890, just two blocks from the Licking River on 13th Street in Covington, Kentucky. During his childhood, the riverbanks of the Licking, Kentucky, and Ohio rivers; the mountainous beauty of the Cumberland River; and the cave country of Versailles near Lexington, Kentucky, became his playgrounds, from which Schulkers would later draw inspiration for his numerous mystery and adventure stories, books, radio plays, and comics, produced from 1918 through the 1940s.

The Seckatary Hawkins stories were first born as weekly installments in the Sunday issues of the Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper, but they were soon syndicated to more than one hundred other newspapers throughout the United States. With their club motto, “Fair and Square,” as guide, the riverbank boys attempt to follow simple values of honesty, patriotism, loyalty to friends and family, and faith in God. Not far away from their clubhouse lies the bigger city of “Watertown,” which represents Cincinnati, Ohio. From here—or from other mysterious foreign locales—come various exotic and troublesome characters to create excitement and mystery for the boys of the Fair and Square Club. Robert Schulkers had played on these riverbanks himself, so he created for his characters a rich and textured topography, brimming with fascinating features that stimulated the imaginations of readers everywhere. For example, Schulkers loved the limestone caves of Kentucky so much that he used caves as the locale for many of the boys’ most exciting adventures; and for most readers of any age, caves evoke a forbidding and foreboding vibe. The enduring appeal of Robert Schulkers’s books, then, owes much to his love of children, his realistic characterization of the boys, and the imaginative and dramatic Kentucky settings he created for them.

Schulkers was also praised for his naturalistic regional dialects and Midwest “riverbank boys” dialogue, so different from writers of the time who envisioned children as miniature adults in speech and mannerisms. He wrote the Seck Hawkins books in this way so that the average Kentucky child, especially, would recognize and enjoy the language common to his or her own experience. Notice the similarity of slang with To Kill a Mockingbird. Schulkers understood and expressed the nuances of the Kentucky character, especially in young boys. There are baseball, campfires, fishing, and friendships. But mistakes are made, and lessons are quietly learned—without cloying lectures—about forgiveness and humility, having compassion and accepting each others’ differences, and how to be a loyal, “fair and square” friend with respect for kin and country. And always the twists and turns of the inevitable dilemmas take them into Kentucky caves, into mysterious underground bunkers and riverboats—in canoes, on horses, scrambling up cliffs, and swinging over treacherous caverns—but always with the rich beauty and majesty of the riverbanks and hills of Kentucky as a backdrop.

Prologue

We boys have had some exciting times around this old Kentucky riverbank. The trouble started a long time ago, and the reason we organized our club was to figure out ways to steer clear of trouble. And that’s how it comes about, too, that all the other boys in and around our town call me “Seckatary” Hawkins. You see, when the boys in our club used to play together on the old riverbank, right down off the main road, we would always get into a fight, somehow or other, with the boys from Pelham, which is just across the river from our town. And the Pelham fellows were pretty rough, too. They built shacks on their side of the river, in which they would meet every day and watch for a chance to “git” us. Well, we didn’t really want to get into any fights; neither did we want to keep away from the riverbank. It’s just natural for a boy to play around a river if he lives near one. And so you see how it was. Never a day passed but what we would have a battle with the Pelham fellows.

So we decided to form a club on our side of the river. The idea made a hit with all of the boys, and they wanted to hold meetings every day, and collect dues, and write down the minutes, and

everything. We wanted to run the club right, just as men run their big clubs, you know. And when it came to picking out someone to write down the minutes of the meetings, they all looked at me, and I knew I was going to be “it.” Of course we were all little kids at that time, and none of us knew how to write very well; and, to tell you the truth, I didn’t know much about spelling myself. So when I wrote down in the book the minutes of that first meeting, I put down that they had elected me to be “Seckatary” (I couldn’t spell “Secretary”), and ever since that time the boys called me Seckatary, and the name has stuck to me even to this day.

Of course we had to have a clubhouse, so one of our club members, Jerry Moore, got his daddy to help us raise a sunken houseboat. He brought down a big derrick and got the houseboat out of the river and put it up on the bank under the trees, and we put logs under it, and braced it so it wouldn’t slip. And for a few days we could not go in it, because Doctor Waters, the only doctor in our town, was a very good friend of us boys, and when he heard about our new clubhouse he came down and said that, since he was the board of health, he would have to nail up the door of the stranded houseboat until it dried out, and after that he would have to fumigate it, and that would take some time, so we would have to play outside until it was ready.

Well, time came when that was all finished, and Doc told us we might go in and take a look. Which we did, and great was our surprise, I tell you, when we saw that good old Doc Waters was certainly a friend of ours. He had cleared out the houseboat and had set up in it a long pine table, with chairs around for each of us boys to sit on, and it was ready for our meetings. Later we got a little stove to keep the place warm in winter, and an old organ, which Lew Hunter, the only real music master in our club, would play while we practiced singing.

So here in this old stranded houseboat we made our headquarters and held our meetings regularly every day after school, and on Saturdays we would be down early in the morning and spend the whole day. And we got along better after we formed our club. We had lots more fights with the Pelhams, to be sure, but we always beat them, and we finally made them a bit afraid of us. However, they brought lots of trouble down around our riverbank, and most always we would be dragged into it. None of it ever made us worry very much, though. Every day I would write down in my book not only the minutes of the meeting, but everything that happened. Most of the fights we had on account of the Pelham boys we laughed at after they were over.

And then came Stoner’s Boy. I am not going to try to tell you the story of this strange fellow, because I might leave out too much if I trusted to my memory. I am going to open to you the minutes book, in which I wrote every day, and let you read for yourself the strange case of Stoner’s Boy.

CHAPTER 1

The Coming of the Gray Ghost

MONDAY.—Us boys come down to our houseboat right after school this afternoon, and it was snowing. Bill Darby had a good fire in the stove, and it was nice and warm in the houseboat. The meeting was held as usual, but nothing special came off. We called the roll and collected the dues. Most of us fellas stayed inside—but Jerry Moore and Hal Rice and Little Frankie Kane went out to have some fun in the snow. Lew Hunter begun to play the organ, and we practiced some songs.

But after a while I could see by the way the fellas looked out the window that they kinda had a feeling like they wanted to git out in the snow and have some fun.

So I says to Lew, “Let’s quit practicing now and go out and make a snow fort on the bank of the river.”

“That suits me,” says Lew. “I ain’t built a snow fort since I was a little fella.”

So we all went down to the bank, but Jerry had beaten us to it. Him and Hal Rice and Little Frankie Kane had a snow fort half built. But we all pitched in and made big balls of snow and patted the balls into blocks, and purty soon we had a nice-looking fort. It had windows in it and everything, and each corner had a little watchtower on it.

I says to Jerry, “Us boys better not let the Pelhams git to it, or it won’t be here very long.”

Jerry says, “Let ’em try it, see what they git.”

It was purty dark by the time we all went home.

TUESDAY.—When we come down today after school, we found our fort all right. The Pelhams didn’t touch it last night, but we noticed that they begun to build one on their side of the river too. Jerry Moore brought down some thin boards, and we braced the inside of the fort so it couldn’t fall in, and then we laid the rest of the boards down and made a floor. We could see the Pelhams on their bank watching, and I says to our capt., “I wonder if they are figgering on coming over.”

Jerry says, “No, they know better than to start anything while we are around.”

Little Frankie begun to cry because it was too cold in the snow fort.

Jerry says, “Well go up in the houseboat and keep warm; there’s a fire in the stove up there.”

But Frankie says, “No, I want to stay here, bring the stove down here.”

Jerry says, “You little simp, how we gonna keep this snow fort from melting if we have a fire inside it?”

So I took Frankie and I says, “Come on, we will go up in the houseboat and play a game of checkers.”

That suited him all right.

WEDNESDAY.—The Pelhams were sneaking around our snow fort when we come down after school today. I was the first one down to the houseboat, so I laid low and waited. Purty soon Jerry and Bill Darby come.

I say, “Lookit the Pelhams, they are gonna bust our snow fort.” Jerry got awful mad. “Hurry up,” he says, “come on and make snowballs, and make ’em hard.”

So we hid behind the houseboat and made snowballs fast as we could. The other fellas come in a little while and helped us. When all of the fellas had come, and we had a big load of snowballs ready, Jerry says, “Now, everybody take a lot of these, and attack them Pelhams, and drive ’em away, and follow ’em as far as your snowballs hold out.”

So out we started.

The Pelhams was supprised; they acted like they wasn’t expecting us so soon. They was carrying a log and just about to let it fall against the snow fort when they seen us coming. For a minit they stood still; then their leader, Briggen hollered, “Beat it quick.”

BRIGGEN

They dropped the log and started off in every direction. Us fellas was right after them. I followed Ham Gardner; he run like a deer, and he started for the river, but I soaked him in the neck with a snowball, and he changed his mind and started for the woods. I sent another snowball after him and hit him on the arm, and he turned sudden and shot out into the woods where the snow was deep, and nobody made a path yet.

I says to myself, “I ain’t gonna git my shoes all full of that snow for a Pelham fella,” so I went back.

Right after supper I was doing my lessons in pop’s library, and I heard a tick-tick-tick on the window. I peeped out. Bill Darby’s face was pushed against the windowpane. He motioned for me to come out. I snuck my coat and cap and went out the side door.

“What you want, Bill?” I asked.

Bill says, “Listen, Hawkins, I got in bad. I broke a window with a snowball this afternoon; the old secondhand store man says if I don’t pay for it he will tell my pop.”

I says, “How come you to break it, Bill?”

He says, “It was while I was chasing a Pelham fella; he run up that way, and I sailed one too high, and it went through the window, and the Pelham fella laughed at me.”

I says, “Well, what you gonna do about it?”

He says, “I gotta pay for it, that’s all.”

I says, “All right, that’s settled then.”

Bill looked kinda disappointed. “No,” he says, “it ain’t settled. I ain’t got no money.”

“Well,” I says, “there’s only one thing to do. Come on.”

We walked down to the houseboat together. It was snowing hard.

We got to the houseboat, and I took out my key to unlock the door when Bill whispers, “Look ther

e.” He pointed to the river. There was something flying down like a gray ghost, covered with snow, carrying an oil lantern. It was a boy. I could see that when he passed by the lighted window of a Pelham shack. He had a dog on a chain, and the dog was running as fast as the boy could skate.

“Who is it?” I whispered.

Bill says, “I don’t know. I guess it’s Little Tim from Pelham; he likes to skate with a light.”

So we went inside, and I lit the oil lamp. Then I went to the loose floorboard, and I got out the tin box in which we keep our money that we collect for dues, which is a dime a week, and which I must take care of. I always get paper bills when we have saved up enough dimes, and I took out a two-dollar bill and gave it to Bill.

“That ought to be enough to pay for the window,” I said, “and if you get any change back, don’t forget, it goes back into this tin box.”

“You know you can trust me, Hawkins,” said Bill.

“I know I can, Bill,” I said, “but it doesn’t hurt to remind a fella y’know. That’s what the money’s for, to help us fellas when we get into trouble, but don’t use any more than you need, ’cause money is a hard thing to get, and an even harder thing to keep once you’ve got it.”

Then I put the box back in our hiding place and we put out the lamp and went out. Just as I was locking the door we seen the gray figger of the skater going back up the river. But he didn’t have no dog.

I says, “It don’t look like Little Tim; he is too big for to be Tim.”

“No,” says Bill, “I guess it ain’t Tim.”

We both stood there and watched him go. He kept on straight up the river toward Watertown, and after he passed the last Pelham shack he disappeared in the dark.

“Funny,” I says, “it don’t seem natural for a fella to be skating on the river at night, and going all the way up.”

Bill didn’t say a word. We started to walk up to the main road, but just then we heard a dog howl. We both stopped.

Stoner's Boy

Stoner's Boy The Gray Ghost

The Gray Ghost